- Wandering the Between

- Posts

- ICMS Kalamazoo '23 and the Peoples Across the Seas

ICMS Kalamazoo '23 and the Peoples Across the Seas

Reflections on my first K'zoo, panicked paper-writing and presenting my ideas

Today’s post is mostly written from the terminal at Detroit airport, where I’ve found myself with plenty of time to reflect on the last few days of conferencing. It was my first time at the International Congress of Medieval Studies held in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and it was a brilliant chance to hear new ideas and ruminate on the state of my own research.

A peaceful coffee and muffin at the Café Liv on the way home.

In some ways, it felt serenely transitional. I’ve recently completed my comprehensive exams, and it was only a couple of days prior to leaving for Kalamazoo that I submitted a final draft of my dissertation proposal. The last five months I’ve spent revising and re-writing my proposal have helped to clarify a lot of ideas that have been bouncing around in my brain - as evidenced by the six or seven drafts which it went through. Writing my paper for the ICMS at the same time as I wrapped up my proposal meant that the conference was the first time I presented myself as a researcher with a serious project, a long-term goal and the skills needed to begin it.

My paper was entitled “‘Two Peoples Across the Sea’: Across the Forth Frontier in the 5th-7th Centuries,” part of a panel on boundary crossing across Britain and Ireland. It stemmed out of a paper I wrote in the fall in our annual medieval seminar, which focused on reuse and landscape in the early medieval Lothians. My presentations were strategic - get responses to my work in different venues, with different approaches, and then enter my research year with bountiful feedback. For ICMS I wanted to talk about my conception of the frontier, the peripheral and central spaces which sit at the heart of my project, and I have to say, it was a surprising success.

The place and powerpoint, taken in a state of anxiety only moments before.

I presented on Saturday, in the afternoon, which meant I could enjoy all the benefits of two and a half days of attending talks and editing my paper. I don’t think I attended a bad panel - from early medieval multilingualism to pollen analysis, Irish ethics to Silk Road slavery, every paper was gold. While anxiety built towards presenting my own work, seeing so many smart people talking passionately about their projects was reassuring. Lunches and evenings were spent meeting people, enjoying local restaurants and sampling interesting beers, explaining my project and interests and hearing about about brilliant research. It was often exhausting - I averaged only about four hours of sleep each night - but invigorating, waking up in the morning with a full slate of interesting events to attend.

When it finally came time to present my work, and the room filled up with a mix of familiar and unfamiliar faces, people I had met over the past few days, folks drawn by the panel, the anxiety ran high. I had only finished my slideshow in the nearby cafe about fifteen minutes before. Giving the presentation was terrifying but I walked through my points and watched the audience, and when it came time for questions, it was everything I had hoped for. A friendly audience asked incredibly insightful questions - some I had the answers for, some I didn’t. I scribbled down in my notebook a dozen fragmentary notes: “get better at barrows;” “long cist transmission?;” “Tay… visibility?” After the talk, folks came up and asked more questions, and by the time I walked out with my heartrate normalizing, I had a real excitement to tackle all these new problems.

So I’m trying to carry that into the summer, as I prepare to embark on a research trip, and the first part of that is returning to my paper and editing it over, fixing my citations and clarifying my wording. Since it was well-received at the conference, I’d love to get feedback from a wider and diverse audience, as I embark on the next stage.

(One note - some maps and illustrations from the original presentation were from publications which I don’t want to reproduce here on a webpage. As with all my citations, I have provided links to the publications which contain these images - apologies!)

“Two Peoples Across the Seas”: Across the Forth Frontier in the 5th-7th Centuries

“We call them [the Picts and Scots] races from over the waters, not because they dwelt outside Britain but because they were separated from the Britons by two wide and long arms of the sea, one of which enters the land from the east, the other from the west, although they do not meet.”

(Bede, Ecclesiastical History i.12, trans. by Colgrave and Mynors)

In the eighth century, in northern Britain, the monk known as the Venerable Bede penned these words as part of his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, building a potent yet simple picture of his contemporary political geography. The Britons dwelled to the south of the two great arms of the sea, and the Picts and Scots to the north. As Walter Goffart has made clear, Bede’s writing was no simple chronicle, but a careful ideological navigation of his own political and ecclesiastical situation, a work that minimized the roles of some and valorized others. Built into the History are many boundary details like this, bits of information on borderlands and frontiers which have shaped our understanding about the early medieval patchwork of kingdoms in Britain. But there are significant problems with Bede’s frontiers as well: they’re an elite view from a single skilled author with several different agendas, and to build a picture of these regions on Bede’s framework alone is to risk misinterpretation. Today, I’m interested in how we can add depth and nuance to these frontier zones by looking at them through different forms of material evidence. In doing so, I hope that we can reconsider some of the dichotomies which Bede introduced and re-center the regions which are so frequently peripheral and divided. Accordingly, in the talk today I will be walking through some of the theoretical questions I’m grappling with about how to best approach a complex and multilayered frontier, before turning towards questions of non-elite movement. This will then lead us into a simple case study, which can remind us how important it is to always re-center frontier zones to ensure that we don’t turn Bede’s rhetorical border into a real methodological wall.

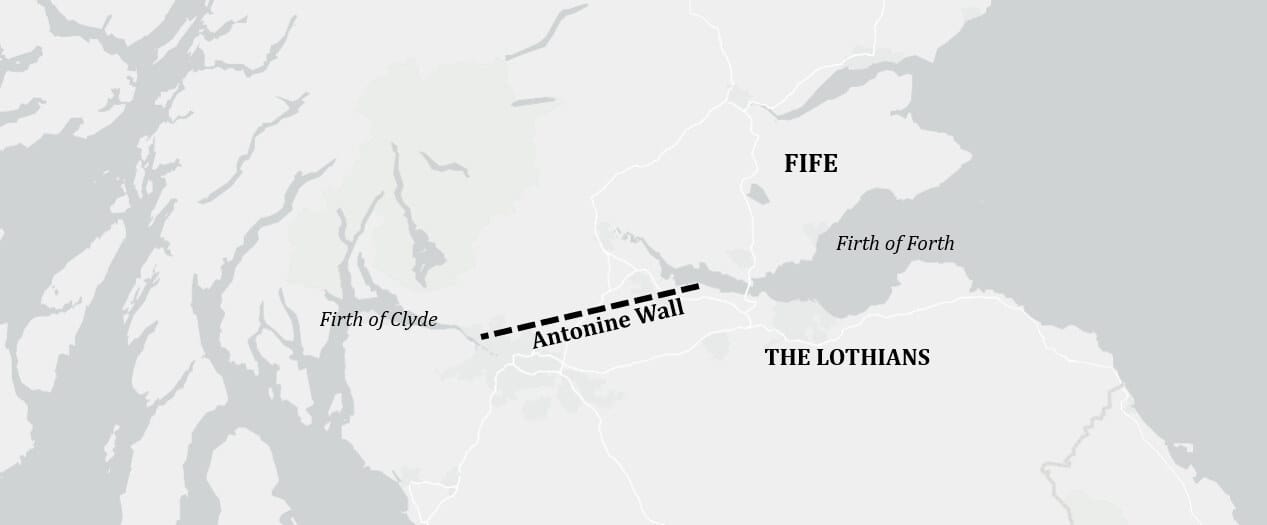

But first, a note on the geography, because I’ve just dropped the odd-sounding word “firth” with no real explanation. The two arms of the sea which Bede mentioned in the previous quote are the Firths of Forth and Clyde, with “firth” denoting a wide estuary in Scots. I want to particularly focus on the former today, the Firth of Forth, which cuts into Britain from the East Coast. The Forth divides the region of Fife – the peninsula in the north – from the region of the Lothians in the south, and nowadays is easily crossed on any one of three modern bridges by car or train in a matter of minutes, a luxury that our early medieval subjects did not have.

The Forth was not impassable in the pre-modern period – and I’ll get back to that later – but it does provide a barrier to casual movement, and the isthmus between the Forth and Clyde has acted as a boundary at several points in human history. The Forth was the eastern anchor of the briefly-lived Antonine Wall under the Romans, and served both as a highway for resupplying Roman forts and an extension of its defenses. Bede, as we’ve seen, considered the Forth and Clyde as fundamental boundaries between peoples, claiming in the History that the Forth was the defining boundary between the lands of the Picts and those of the Angles. The early medieval battles between Picts and Anglian Northumbrians around the Forth which Bede describes have built an image of the estuary as a major and violent boundary between two powerful elite dynasties.

However, as the archaeologist A. Asa Eger has pointed out in his studies of the Islamic-Byzantine frontier, such borderlands are rarely so simple. The rhetorical lines in the sand which writers like Bede describe must sit next to legal boundaries, violent raids, cultural differences and settlement patterns, all of which also built spatial peripheries. We can’t dismiss any of them – even Bede – too quickly, as Eger has argued, because all of these different layers comprise the complex frontier space. To try to “truth check” one layer against another risks losing sight that both the texts and material evidence reflect aspects of a larger multilayered and multivalent space. This framework means that one of the biggest questions underpinning my research is how we can best access the non-elite frontier spaces, the lifeways of everyday people who lived along these estuaries and for whom the waters of the Forth were a vibrant and living space.

The Forth and East Lothian as viewed from Arthur’s Seat

I argue that one of the best ways we can access these worlds is through the material record, which often preserves non-elite lives better than many of our texts, and in turn, give us the ability to see commonalities across the Firth of Forth that point to communication and connection. I am not claiming that there was no frontier on the Forth, indeed, the existing archaeological scholarship seems to show many material realities corresponding with Bede’s rhetorical early medieval boundary. Adrián Maldonado, whose excellent map you can view here, has discussed this in terms of burial practices, where we can see that the Forth seems to divide a southern bank dominated by stone-lined “long-cist” graves from a northern zone defined by barrow burials. Similarly, Alice Blackwell has examined early medieval metalwork, and has noted that Anglian-style metalwork is found commonly in the Lothians but is conspicuously absent in Fife, which she attributes to “deliberate political statements.” Both Maldonado and Blackwell have argued strongly against mapping these uncritically onto ethnic terms like “Pictish,” “Christian,” or “Northumbrian,” but clearly communities in the Lothians and Fife were looking towards different practices in the fifth through seventh centuries, practices that often distinguished them from the people across the waters.

This idea of two different material cultures seems natural if we look through Bede’s lens, but to the contrary, the waters of the estuary do not appear to have been impermeable to the people of the fifth through seventh centuries. Mechanisms of cultural interchange require movement, and movement is critical to frontier studies, as so much of what defines the peripheral is based on concepts of distance, inaccessibility, and controlled mobility. As such, these mechanisms of human travel are a vital part of understanding any frontier. We know that watery travel was not only available to late Roman and early medieval people on the Forth, but was often a more efficient travel method, especially along coastlines and riverways. There has been a considerable amount of scholarship on the connective power of watery spaces over the last few decades, which have demonstrated that watery spaces often functioned as heartlands and highways for elite dynasties in northern Britain. The Roman fortifications along the Forth – such as Inveresk or Carriden – were designed to help resupply frontier garrisons, which suggests strong sea supply routes, and a bevy of prehistoric and early medieval log boats discovered along the rivers of the region make it clear that watery travel was available to different levels of society. Prehistoric evidence from East Lothian shows that deep-sea fishing was being done at the Forth in the Iron Age, suggesting that even in the centuries prior to the early medieval period, the local people knew how to access and exploit deep-sea natural resources. Sixth-to-seventh-century burials on the Isle of May, in the middle of the Forth, would have required watery travel from the mainland, and Christopher Ferguson has argued that the southern banks of the Forth could have been quickly reached by sailing from Northumbrian central sites such as Bamburgh – much faster than via land. Textual references also support this connectivity: Bede and the sixth-century monk Gildas reference Pictish skin-boats and ships raiding past the Roman frontiers of the fifth century, and the Life of Saint Cuthbert mentions him sailing to the Niduari of Fife in the seventh century from farther south. From the voyages of saints like Cuthbert to the log-boats which enabled local travel, it is clear that the Forth was no barrier to the people of the first millennium, and that these crossings were not limited to the elite alone.

The distant Bass Rock and Berwick Law in East Lothian viewed from the Forth

This clear evidence of watery connectivity, then, can provide us with a glimpse into how non-elite mechanisms of cultural transmission worked in the region. This, in turn, can help us nuance the picture of the Forth as a fundamental barrier, and rather center it as a space of connected communities. Excellent work has been done in the last several decades on the movement of secular and ecclesiastical elites and their trade goods across bodies of water. Scholars have looked towards fosterage, exile, and conversion as major mechanisms of cultural exchange, focusing largely on the textually-visible kings and saints who moved around our early medieval world. However, the connectivity of the Forth suggests that such travel would not have only been restricted to such elites, and the day-to-day travel of non-elites across the Forth would have made it a potent space for cultural interchange between communities on the north and south banks.

With this clear multi-level connectivity, we can return back to the metalwork and burials we briefly examined earlier, and we might now be surprised to see such differing traditions of evidence on the north and south banks. We shouldn’t be! The most visible surviving evidence from the region is generally high-status, requiring investment and authority which would have been unavailable to many of the people living in the region. Blackwell and Maldonado have argued that burial practice and metalwork are both ways that people formed identities, either by wearing metalwork styles which signaled connections or by burying their dead in similar ways to their community members. But such metalwork, which provides one of our clearest dividing lines between the material culture of Fife and that of the Lothians, is a necessarily high-status good. The access to precious metals, gems or glass, and the tools needed to craft brooches and sword-fittings ensured that only elites would be able to access such items. We know that such high-status metalwork was being produced in Fife, as excavations at Clatchard Craig have unearthed molds for casting brooches, but our only examples from the region come from a high-status elite hillfort in northern Fife. This fits with other evidence of elite metalworking centers in Scotland more broadly, which seem to have been concentrated at power centers such as Dunadd in the west. Such metalwork would also have been restricted in its visibility to the early medieval person, being displayed largely when the elites wearing the brooches would have been present and visible, making them a far more inaccessible item for the non-elite. It’s therefore not surprising that our metalwork finds show stark differences in affiliation diverging at the Forth, as the wearers of such brooches and pins would have had good reasons to signal affiliations with regional dynasties.

In contrast, other forms of evidence from the region would have been more accessible and local in their production, making them valuable evidence for the non-elite. Stone monuments, of which the Forth has many, required highly skilled craftsmen, but the material for contemporary monuments in the region seems to indicate that they were drawn from local quarry sources. This would have made stone monuments cheaper and more local than the metals or gems which required refining processes such as smelting or cutting. Stone sculpture was meant to be displayed in at least semi-public spaces, at monasteries or in the open air, where they could be viewed by passerby. This means sculptured stones bridge a gap between the elite and non-elite, as monuments demonstrating skill and patronage which would have been visible and accessible to the local non-elite.

It is therefore unsurprising given the permeability of the Forth frontier that sculptured stones show evidence of cultural interchange that metalwork does not, and I want to focus on a specific case study of this in the latter part of my paper today. There has been a small but vigorous body of scholarship comparing sculptured stone patterns and motifs across the Forth frontier, especially in recent years, and it has become increasingly clear that our early medieval stoneworkers could move between styles with a great deal of flexibility. Christina Cowart-Smith has looked into some of this with her work on high crosses in Northumbria, discussing eighth- and ninth-century cross fragments from around the Forth in terms of sophisticated sculptors unafraid to combine northern and southern styles and push boundaries. The famous Saint Andrews Sarcophagus from Fife has seen extensive art-historical analysis which has often connected its motifs to more southerly examples. These comparisons often focus on the identification of style influences, but there is a lot of potential for thinking about what these stones can tell us about sculptors, their local communities, and how such influences move.

The imposing Hilton of Cadboll symbol stone in the National Museum of Scotland - note the key-pattern in the crescent!

In the Forth area, we see several differing traditions of sculptured stone in the early medieval period, and many of the stylistic choices seem to broadly conform to the Forth boundary, perhaps reflecting differing patronage networks. Nearly all stones bearing the Pictish symbol system, for instance, have been found north of the Forth, and all stones with Roman-inspired Latin inscriptions have been found to the south. Certain decorative motifs, such as key-pattern, prevail north of the Forth, and others, such as freestanding high-crosses, dominate farther south. Given our textual border, it is tempting to think about the exceptions – like the two Pictish symbol stones south of the Forth – as outliers, evidence of invasion and occupation, and this has been raised as an explanation for these two Pictish stones. But as Katherine Forsyth and Cynthia Thickpenny have effectively argued, the idea that the southerly symbol stones represent some outlying Pictish military activity is flawed. They argue that these symbols and designs must have held recognizable meaning to the people living around them, meaning that they represent locally-understood practices. Combined with the time-consuming process of incising stones with these symbols, we should already be considering these symbol stones as products of their local landscapes, and not as ephemeral evidence of the conflicts which our sources such as Bede emphasize.

The locations of the two Pictish symbol carvings south of the Forth

Categorizing such stonework as outliers does not only risk fitting our stonework into a risky textual framework, but it also has significant ramifications for how we organize and compare our stonework. The designation of the two southern Pictish symbol stones, for instance, has sometimes led to them being considered together as a pair, despite the fact that they were found nearly eighty miles apart. Additionally, this has prevented them from being compared to symbol stones much closer to them – such as those right across the Forth. One of the outliers, shown here, was found in Edinburgh, very close to the waters of the estuary and known early medieval settlement sites. The stone bears some of the simplest carvings in the symbol system, with a crescent-and-v-rod with no terminals, and a likely double-disc and z-rod. The simplicity and lack of any associated cross carving have previously led scholars to assign it to an early date in older classification systems – generally the seventh or eighth centuries. However, new radiocarbon dating from Gordon Noble and others has pushed the symbol chronology earlier and earlier, with the simplest incised carvings being potentially as old as the third or fourth centuries. Under this chronology, the Edinburgh stone could represent an early example of such carvings.

If we re-center the Forth and consider the Edinburgh stone alongside symbols directly across the water, we see some parallels. The Wemyss caves in southern Fife face out out into the Firth of Forth, and are filled with a variety of simple incised carvings, including many from the Pictish symbol system. Given existing interpretations of the origins of the Pictish symbol system potentially farther north, the Wemyss carvings have been considered as peripheral or ephemeral; Graham Ritchie and Stevenson suggested they might be the work of itinerant metalworkers, given similarities to symbols on the nearby silver treasure from Norrie’s Law. The floor layer in one of the Wemyss caves has been radiocarbon dated to the third or fourth century, which Noble has noted matches the early symbol dating of more northerly examples. Comparing the Wemyss cave carvings to the Edinburgh stone, then, might suggest that we are seeing a very early experimentation with such symbols far from the traditional ‘cores’ of such iconography, experimentation that spanned the Forth rather than ending at it.

We should be careful not to fit this picture of cultural interchange in the frontier zone solely into an elite picture of the core and periphery. The accessibility of the Firth of Forth made it a space for the non-elite too, and for many of the people living along the estuary, it must have formed a more potent center than any distant hillfort or king. The incised symbols of Wemyss and Edinburgh are evidence of early commonalities across the borderline, and show the potency of re-centering bodies of water in order to build a better multilayered frontier.

I would like to close out my paper today by discussing some of the directions I hope to take this work in during the next few years of my dissertation-writing. Sculptured stone only represents one small part of what I hope to do, and I do not intend to confine myself to just the Firth of Forth. It has become increasingly clear that the material evidence of human exploitation and experience of the landscape represents one of the best sources of evidence for understanding the non-elite frontier. As such, my next big questions for the region are:

How were the lifeways of the people living in these estuaries shaped by the local natural resources and ecologies?

How did people access, control, and exploit these resources in their daily lives?

How did they build meaningful human landscapes in these regions, complete with monuments and settlement and invested with memory?

How did they encounter and interact with the far more ancient ruins in their midst, physical markers of the past?

I hope to find the answers to these questions and many more over the next few years. Thank you for your time.

Enjoy early medieval history? Go check out some of my favorite medieval subject writers:

Fiona Campbell-Howes, Becoming an Early Medievalist

Tristan, SeaxEducation

Samuel Clarke, Mīn Webblēaf

Florence Scott, Ælfgif-who?

Bibliography, Used and Recommended

Bede, The Venerable. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Edited by Bertram Colgrave and R. A. B Mynors. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

Goffart, Walter. The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550-800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Eger, A. Asa. The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier: Interaction and Exchange Among Muslim and Christian Communities. London: I.B. Tauris & Co., 2017.

Maldonado, Adrián. “Burial in Early Medieval Scotland: New Questions.” Medieval Archaeology 57, no. 1 (2013): 1–34.

Blackwell, Alice. “A Reassessment of the Anglo-Saxon Artefacts from Scotland: Material Interactions and Identities in Early Medieval Northern Britain.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, 2018.

Edmonds, Fiona. Gaelic Influence in the Northumbrian Kingdom: The Golden Age and the Viking Age. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2020.

Petts, David. “Coastal Landscapes and Early Christianity in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria.” Estonian Journal of Archaeology 13, no. 2 (2009): 79–95.

Edmonds, Fiona. “Barrier or Unifying Feature? Defining the Nature of Early Medieval Water Transport in the North-West.” In Waterways and Canal-Building in Medieval England, 21–36. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Bishop, M.C., ed. Roman Inveresk: Past, Present and Future. Duns, UK: Armatura Press, 2002.

Bailey, Geoff B. “Excavation of Roman, Medieval and Later Features at Carriden Roman Fort Annexe in 1994.” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 127 (1997): 577–94.

Russ, Hannah, Ian Armit, Jo McKenzie, and Andrew K G Jones. “Deep-Sea Fishing in the Iron Age? New Evidence from Broxmouth Hillfort, South–East Scotland.” Environmental Archaeology 17, no. 2 (October 1, 2012): 177–84.

James, Heather F, and Peter Yeoman. Excavations at St Ethernan’s Monastery, Isle of May, Fife 1992-7. Perth: Tayside and Fife Archaeological Committee, 2008.

Ferguson, Christopher. “Re-Evaluating Early Medieval Northumbrian Contacts and the ‘Coastal Highway.’” In Early Medieval Northumbria: Kingdom and Communities AD 450-1100, 283–302. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011.

Gildas. The Ruin of Britain and Other Works. Translated by Michael Winterbottom. Phillimore & Co. Ltd., 1978.

Anonymous, and The Venerable Bede. Two Lives of Saint Cuthbert: A Life by an Anonymous Monk of Lindisfarne and Bede’s Prose Life. Translated by Bertram Colgrave. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1940.

Breeze, Andrew. “St Cuthbert, Bede, and the Niduari of Pictland.” Northern History 40, no. 2 (2013): 365–68.

Noble, Gordon, Nick Evans, Martin Goldberg, and Derek Hamilton. “Burning Matters: The Rise and Fall of an Early Medieval Fortified Centre. A New Chronology for Clatchard Craig.” Medieval Archaeology 66, no. 2 (2022): 266–303.

Lane, Alan, Ewan Campbell, and J. Bayley. Dunadd: An Early Dalriadic Capital. Oxford: Oxbow, 2000.

Cowart-Smith, Christina. “The Abercorn Assemblage: New Insights into the Sculptural Repertoire of a Central British Monastery.” Conference Presentation presented at the Common Ground: A Conference in Honour of Anne Ritchie, March 5, 2022.

Foster, Sally M., ed. The St Andrews Sarcophagus: A Pictish Masterpiece and Its International Connections. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1998.

Forsyth, Katherine. “Hic Memoria Perpetua: The Early Inscribed Stones of Southern Scotland in Context.” In Able Minds and Practised Hands: Scotland’s Early Medieval Sculpture in the 21st Century, 113–34. Leeds: The Society for Medieval Archaeology, 2005.

Thickpenny, Cynthia. “Making Key Pattern in Insular Art: AD 600-1100.” Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, 2019.

Forsyth, Katherine, and Cynthia Thickpenny. “The Rock Carvings.” In The Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged: The Discovery of a Royal Stronghold at Trusty’s Hill, Galloway, 83–102. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2017.

National Record of the Historic Environment. “Edinburgh, Princes Street Gardens | Canmore.” Canmore. Accessed December 10, 2022. https://canmore.org.uk/site/52135/edinburgh-princes-street-gardens.

Noble, Gordon, Martin Goldberg, and Derek Hamilton. “The Development of the Pictish Symbol System: Inscribing Identity Beyond the Edges of Empire.” Antiquity 92 (2018): 1329–48.

Graham Ritchie, J.N., and John Stevenson. “Pictish Cave Art at East Wemyss, Fife.” In The Age of Migrating Ideas: Early Medieval Art in Northern Britain and Ireland, 204–8. Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland, 1993.